Game Addiction Criteria May Misdiagnose Gamers

At the beginning of 2017, I broke down a research paper demonstrating the positive mental health benefits of online gaming. The findings of this paper questioned the validity of the diagnostic criteria for Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) as there did not appear to be a straightforward relationship between playing video games and being addicted to games.

The lead author of the paper recently published a new piece of research which focuses on assessing the diagnostic criteria for IGD. In layman’s terms, they want to know whether people who may be diagnosed with IGD actually look like they may suffer from IGD.

As the author has previously approved of my breakdowns of their research, I am once again diving into the waters of IGD research to share the current research climate with you all.

There is a summary at the end if you do not wish to read everything. Please enjoy!

Introduction

In my previous article on The Psychology of Gaming Disorder, I discussed how Gaming Disorder would likely be included in the World Health Organisation’s ICD-11 without any form of testing or investigation.

Internet Gaming Disorder, separate from Gaming Disorder, has been included in the DSM-V’s ‘Condition for Further Study’ category for a number of years. This means that before Internet Gaming Disorder can officially be diagnosed, researchers must first explore the validity of this criteria. This is achieved by developing questionnaires based on the criteria, conducting research with these questionnaires, investigating its prevalence in the general population, and comparing it with other measures such as depression questionnaires.

This is exactly what this current study is doing. However, as IGD has received a number of valid criticisms, the authors make a number of key arguments in the introduction which cement the need to conduct the complicated statistical analyses that they later conduct.

One criticism that IGD has received is its similarities to criteria for gambling addiction. This is viewed as a logical fallacy as being excited to leave work to sit in a lonely dark room and gamble your money away is not inherently similar to being excited to leave work and hunt monsters with your friends. This leads to fears that current game addiction criteria simply isn’t good or sensitive enough to detect what online gaming addiction actually looks like:

At this point, it is still unclear if all criteria for IGD in DSM-5 actually predict truly problematic behavior in the context of video gaming, or whether they might simply capture high engagement and a healthy interest in gaming

Conversely, there are also fears that the criteria is overly sensitive.

This has significant importance for the utility of instruments used to assess IGD. Because all symptoms are evaluated equally, engaged video gamers (fans of video games who play heavily but do not experience significant problems) may end up being classified as having IGD on the basis of these weak symptoms alone.

Note that the quote says ‘for the utility of instruments…’. This is due to the fact that if IGD is recognised as a mental health disorder, it cannot be diagnosed unless it is debilitating to the person’s quality of life. However, this distinction is typically not present in research.

Hypothetically, I could take an IGD questionnaire and answer that I think about games at work, become sad when I don’t get the time to play games, and stay up late from time to time playing games. Despite these behaviours not impacting my life or career, I could be flagged as a potential candidate for game addiction. I then become a statistic in research which demonstrates the ‘prevalence’ of IGD in our society and the need to legitimise it as a mental health disorder.

The authors of this paper are not satisfied with this approach to validating the criteria for IGD. Instead, they approach validating the criteria for IGD in two ways.

The first way is to distinguish between ‘symptoms’ of IGD and ‘problems’ of IGD. To elaborate on these:

- Symptoms: Lack of control over game playing, often thinking about gaming, craving gaming, gaming modifying your mood, having an increased tolerance to gaming (wanting to play more) and withdrawal symptoms from gaming.

- Problems: Problems with relationships, problems with school/work, or other such negative consequences.

By using this distinction, it is possible to gauge whether symptoms of IGD actually correlate with problems associated with IGD. This way, we can explore whether factors such as thinking about gaming and being sad about not being able to play games actually leads to negative consequences.

The second way is achieved quite simply by how the data is analysed. The data in this study is analysed using Latent Class Analysis, a data analysis strategy that naturally groups people together based on their responses and behaviours (more on this in ‘Data and Analysis’). By correlating symptoms and problems together along with wider problems such as life difficulties scores, we can get a fuller understanding of what types of gamers there are in relation to gaming, wellbeing and addiction.

One gamer group that the researchers hypothesise will emerge is an ‘Engaged Gamer’ group. An Engaged gamer will love video games and will often be preoccupied with gaming, but will suffer little negative consequences as a result of their love of gaming.

Now that we know the rationale, let’s dive into the study.

Data and Analysis

The data for this study comes from the EU NET ADB study, a study of internet and gaming addiction conducted in seven European countries. The initial sample in this study was 13,708 participants aged between 14-18, with the final sample being 7,865 participants due to only including young people that played video games at least once per month. Although this is a very healthy participant pool, the age range can be criticised for not exploring gaming behaviours outside of the home environment which is often dictated by parental control. This is also an important factor that will be discussed later.

The scales used in this study include:

- Internet Gaming Disorder scale (AICA-S): This scale is designed to measure the symptoms and problems of IGD outlined above. In this scale, a score of 7-13 is considered ‘at risk’ of IGD and above 13 is indicative of someone having IGD.

- Psychological wellbeing: The Youth Self-Report scale was used here to assess mental health, social participation and daily functioning, both positive and negative. Positive functioning includes positive social, academic and activities competencies, while negative functioning includes aggressive behaviour, anxiety, attention problems, defiant behaviour, social problems, somatic problems, thought problems and depression.

As previously mentioned, groups of gamers will be identified using Latent Class Analysis (LCA). I will paste my description of LCA from my previous IGD study breakdown:

In LCA, rather than creating arbitrary categories and collecting data on them, you collect your data and use it to create data-driven, person-centred categories.

Let me explain. I ask a group of people whether they play six games: Street Fighter, Final Fantasy, Tekken, Call of Duty, Halo and Dragon Quest. I run an LCA using all of this data. The LCA then tells me that it looks like there are three categories that exist in this data. Category 1 is people who play Street Fighter and Tekken, Category 2 plays Call of Duty and Halo, and Category 3 plays Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest. I then label Category 1, 2 and 3 ‘Fighting game players’, ‘First person shooter players’ and ‘JRPG players’ respectively. Voila, I have naturally-occurring, data-driven categories.

Based on the analyses of IGD criteria and psychological wellbeing, there are six main hypotheses:

- Classes which experience a high number of symptoms and problems will meet the criteria for IGD.

- Age, sex and country will be associated with class.

- The IGD class will have poor psychosocial wellbeing.

- The ‘Normative’ class (i.e. the least amount of symptoms and problems) will have the weakest association with poor psychosocial wellbeing.

- Classes with moderate to high problems will have poor wellbeing in comparison to the ‘Normative’ class.

- The hypothesised ‘Engaged Gamers’ class will not have poor psychosocial wellbeing.

Results

From the Latent Class Analysis, five classes of gamer emerged. The largest class was the predicted ‘Normative’ class (61.8%), a group of people with low scores on both symptom and problem criteria for IGD. The smallest class was labelled the IGD class (2.2%). This class was high in both symptom and problem criteria for IGD.

The remaining three classes tell an interesting story for the IGD criteria. The second largest class identified was the ‘Concerned’ class (23.6%). In this class, scores on the symptom criteria were mostly similar to the Normative class, but they differed in key symptoms. In particular, ‘Concerned’ gamers felt that they played games for too long, struggled to limit their gaming and used gaming to escape negative feelings. These gamers felt that their gaming disrupted domains such as school work and spending time with family.

The ‘At-Risk’ class (5.1%) experiences some IGD symptoms, but remains well below that of the IGD class. However, they experience the same amount of problems as those in the IGD class. In particular, the At-Risk class feel an impaired level of control when it comes to gaming.

Finally, as predicted, an ‘Engaged Gamer’ class emerged (7.3%). Engaged gamers experienced symptom criteria at a similar level as the At-Risk group (e.g. usually thinking about games), but experiences far, far fewer problems.

Very interesting gender differences emerged regarding differences in group membership. As previously stated, scores of 7-13 on the AICA-S indicate that someone is at risk of developing IGD, while above 13 indicates the presence of IGD. For males, the mean score on the IGD class was 17.8, meeting the criteria for IGD. However, the mean score for the female IGD group was 10.6, meaning that these women who appear to have IGD would be identified as at-risk in a clinical setting rather than being diagnosed with IGD. I will also note here that males were more likely to be Engaged gamers than females.

The group means for the Engaged class and Concerned class continue the interesting story of the IGD criteria. The class mean for the Engaged class was 7.6. This means that despite experiencing far, far fewer problems than the At-Risk or IGD group, these gamers would be identified as at-risk of developing IGD. Conversely, the Concerned group wouldn’t be identified as at-risk as the class mean did not reach 7 despite feeling that gaming interfered with their life.

In a nutshell, this means that the people who do not experience problems would be classified as at-risk, and the people who may experience problems are not classified as a risk.

In regards to mental wellbeing, the Normative group was indeed identified to have the best mental wellbeing. The IGD, At-Risk and Concerned groups had poorer mental wellbeing than the Normative group with small to medium effect sizes.

The Engaged group had the second best mental wellbeing of the five groups, but correlations between poor mental wellbeing and being an Engaged gamer were flagged as significant. However, these effect sizes were tiny. Compared to Normative gamers, Engaged gamers were only 4% more likely to experience poor mental wellbeing and 5% more likely to have impaired levels of activities (e.g. spending time with friends and family).

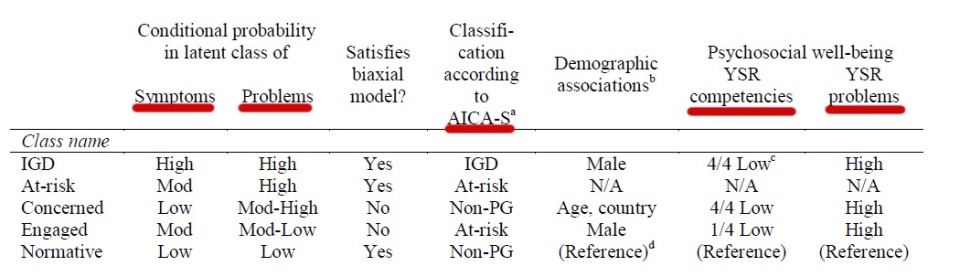

All of this can be summarised in one diagram below.

Discussion

In this study, five types of gamers were uncovered using criteria for Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD): Normative, IGD, At-Risk, Concerned and Engaged.

Possibly the two most interesting findings in this study relate to the constructs of Engaged and Concerned gamers. Engaged gamers have the second best mental health scores of the five groups and do not tend to suffer debilitating consequences due to their gaming, but would be classified as at-risk of developing IGD using the current criteria.

Two things can be argued from this finding. The first argument is that heavily borrowing from gambling addiction criteria to create gaming addiction criteria doesn’t seem to be effective for people and can misclassify people who love playing and thinking about games. To recycle the analogy from the introduction, thinking about hunting monsters after work is not inherently similar to thinking about gambling your paycheque away in a dark room.

The second argument is the cause-effect relationship of the 4-5% increase in poor mental wellbeing in this group. In the researcher’s previous work, we see that online gaming is beneficial for people who lack social groups offline. For these young people, gaming could simply be a way to alleviate pre-existing poor wellbeing and connect with others socially rather than something that creates poor wellbeing. This means that we would need to focus on their mood and wellbeing rather than focus on their gaming.

The Concerned class, pardon the pun, concern me. These people are not as preoccupied with gaming as the Engaged gamers, but report more negative consequences to gaming. I previously critiqued the study for only featuring a sample age of 14-18, and it is in this group of young people that I feel the limitations of the sample age. I say this as I can interpret the Concerned class in two ways:

- Concerned gamers don’t find as much joy in gaming as Engaged gamers do and simply game as a distraction from everyday life to a dysfunctional degree.

- Concerned gamers actually play games at a normal level and have biased perceptions of the disruptive effects of their gaming due to overbearing parenting.

The latter is something that I feel would be most pervasive in an adolescent population. Young people could be playing games in their spare time at a normal level, but even this normal level would frustrate parents that would rather see them invest their time elsewhere.

I would like to see this study replicated in an older sample. Based on the above arguments, Concerned gamers either don’t need any help at all, or very much need help. They would either benefit from a diagnosis of Internet Gaming Disorder to enter a healthy treatment programme, or a diagnosis would be a large waste of time and resources.

Overall, this study shows that an overreliance on gambling addiction criteria to create gaming addiction criteria does not seem to be effective. This approach not only erroneously misclassifies young gamers as at-risk for an addiction, but young people who may actually be addicted are not being classified as such due to failure to reach certain diagnostic criteria.

It seems that more work needs to be done, and I look forward to breaking it down for you all.

Thank you very much for reading and please have a nice day!

Summary

- Before Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) can be recognised as a mental health disorder, researchers must first assess how accurate and valid the diagnostic criteria is.

- This study wishes to assess IGD in relation to its symptoms (e.g. thinking about games) and its problems (e.g. spending less time with loved ones). In particular, the study explores how symptoms and problems relate to each other to form different groups of gamers (e.g. a group that is high symptoms, low problems).

- These groups are identified using Latent Class Analysis, a person-centred data analysis strategy which groups people together based on their responses to the IGD diagnostic criteria. These groups were then correlated with measures of mental wellbeing.

- Data was analysed from a European study of seven countries featuring 7,865 adolescents aged between 14-18.

- Using the IGD diagnostic criteria, five groups of gamers were identified: Normative, IGD, At-Risk, Concerned and Engaged. Concerned gamers experience relatively low symptoms and high problems, while Engaged gamers experience high symptoms and low problems.

- Despite the belief that gaming is detrimental to their quality of life, Concerned gamers do not meet the criteria for IGD. Despite Engaged gamers experiencing little change to their quality of life, Engaged gamers meet the criteria for being at-risk of developing IGD.

- It is more difficult for girls to meet the diagnostic criteria for IGD than boys. Boys are also more likely to be Engaged gamers.

- All groups apart from Normative gamers are associated with poorer mental wellbeing, but this association is particularly weak for Engaged gamers.

- Engaged gamers are argued to be people who love video games and this does not detract from their quality of life. However, due to overreliance on gambling addiction criteria, they may be misclassified as at-risk for developing IGD.

- Conversely, Concerned gamers may be people who experience little joy from gaming and need help, but the diagnostic criteria does not recognise these people as needing help. However, more research needs to be conducted on Concerned gamers in older populations due to potential biases such as overbearing parents.