How to Improve Online Gaming Behaviour

With the ever-increasing popularity of online gaming, the topic of online gaming behaviour and harassment is gaining more attention than ever. It is common to see editorials on the negative side of online gaming, but these editorials typically will not feature any helpful information on how to combat the problem. BullyHunters, an effort to reduce female sexual harassment in gaming, was recently outed as an unhelpful and sinister marketing campaign.

I consider this to be the final nail in the coffin for what has been a generally unproductive and unhelpful conversation about online gaming behaviour. I have taken it upon myself to use research and psychology to inject some productivity into the discussion. This article will feature information for both players and game developers on how to deal with and reduce negative online behaviour.

There are times where I may use the word ‘harassment’ to avoid the repetitive nature of writing ‘negative online behaviour’. To be clear, I do not consider things such as banter between friends and helpful critique (e.g. “You need to use this ability more”) as harassment. If you would like a point of reference, think of something such as “Worthless idiot, uninstall and kill yourself”.

As usual, there will be a summary at the bottom if you do not wish to read everything. Please enjoy!

Just Don’t Look: The Power of Blocking/Muting

The most commonly referenced anti-harassment tool is the ability to block and mute players in-game. I typically see people wanting to end the conversation here, stating “Mute, block, move on, that’s it”. I completely agree that blocking and muting are powerful tools, but I would like to approach this from two perspectives: why blocking and muting are so powerful, and why it might not work for everyone.

The unfortunate reality of the world is that people can have the desire to inflict harm on others. A lot of research attention has been paid to contextual, individual and socioeconomic factors that can influence the desire to bully. These factors can include: behavioural problems, being antisocial, poor mental health, poor family circumstances, having low income and having low academic achievement (Cook et al., 2010; Ferguson et al., 2009; Vaughn et al., 2010; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2000; Ferguson et al.; Barboza et al., 2009; Bradshaw et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2009).

While these factors are related to someone’s desire to hurt someone, there is a vital difference between offline bullying and online gaming harassment – the social context. Social Ecological Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) argues that our behaviour is influenced by our social contexts and relationships with others. So why is the social context important?

Previous research has shown that in offline bullying, around 2-4 peers are present in 85-88% of bullying cases (O’Connell et al., 1999; Pepler et al., 2010). This adds an additional contextual layer as we go from ‘causing harm’ to ‘causing harm with an audience’. Research has also shown that peer audiences tend to ‘enjoy’ the show and either watch or join in themselves (Craig & Pepler, 1998; O’Connell et al.).

For the bully, the audience’s enjoyment helps raise their social status in the peer group and acts as encouragement to do it again (Swearer & Hymel, 2015). For the person being bullied, their social status in the peer group is reduced and they have to choose whether to retaliate or quietly take the abuse. If they retaliate, they risk further abuse that may even turn physical. If they remain quiet, the damage to their social status in the peer group still happens regardless.

Compare this to the random nature of online matchmaking in games. You are paired with people to whom you have no obligation to and do not share a peer group with. You are not being insulted by someone who is trying to elevate their social status in school or try to put on a show for your class. You are being insulted by someone you don’t know, you will never know and in front of people you do not know who simply wants a reaction from you. There is no threat to your social status or physical wellbeing.

If you mute and/or block them, you do not give them that reaction. The power dynamic shifts from them holding the power to you holding the power. You do not give them anything that they want and you are not acknowledging their presence. ‘Do not feed the trolls’, a long-standing internet mantra, will work in online gaming if you let it.

Key words: if you let it.

Back in my article on The Psychology of Difficult Games, I wrote about differences in people’s processing of behaviours and emotions. I stated that people who internalise their behaviours and have a high locus of control are more likely to self-flagellate and feel responsible for situations respectively (Bornstein et al., 2010; Rotter, 1966).

One of the most prominent theories in cognitive psychology is schema theory (Piaget & Cook, 1952). Schemas are a unit of collected knowledge and experience that guide our understanding of and reactions towards the world. The most basic way to think of a schema is a filing cabinet full of paper: the cabinet is the schema and the paper is our knowledge and experiences.

Unfortunately, this does not mean that everything that occupies a schema has a logical and rational basis. Those who internalise their behaviours or suffer from poor mental wellbeing may have a schema labelled “Reasons Why I’m A Failure” or “Reasons Why I Should Kill Myself”. It doesn’t matter if they do not respond to the person, the fact that they have seen their comment means another piece of paper gets added to the filing cabinet to fuel their self-flagellation. If they have a high locus of control, they are more likely to blame themselves for the interaction rather than it being the perpetrator’s fault.

We have demonstrated that muting and blocking are online harassment tools that can empower people, but vulnerable people may use what they see as an excuse to self-flagellate and believe they are worthless. We know how to deal with harassment, but is it possible to reduce it?

Let’s look at the research.

The Optimus Experiment

Before I dive in, I would like to introduce some research from occupational psychology, the study of people in the workplace. As occupational psychology involves keeping workers happy and work output high, it makes sense to test such proverbs as “you catch more flies with honey than vinegar”. Should you be kind to maximise work output, or do you need some good ol’-fashioned fear and force to get workers motivated?

When the workplace includes someone who is brutal, harsh and overly critical, this results in lower workplace performance and more absenteeism (Harris et al., 2007; Tepper et al., 2006). This finding was later used in the television show Parks and Recreation for comedic purposes: although an employee completed more filing when berated and put under pressure, nearly all of the filing was incorrect due to stress.

The increased likelihood of failure under harsh criticism and stress can be applied to online gaming. Kwak, Blackburn and Han (2015) analysed a database of over ten million online reports from the online game League of Legends. They found that when a match included reports of ‘offensive language’ and ‘verbal abuse’, the team of the offending player was 50% more likely to lose.

So we have established that people may perform worse under harsh criticism and stress and that this may also apply to online gaming. How can this be used to curb online harassment?

Returning to League of Legends, I would like to introduce Dr Jeffrey Lin, a cognitive neuroscientist and the creator of The Optimus Experiment, an exploration into reducing negative behaviour in League of Legends.

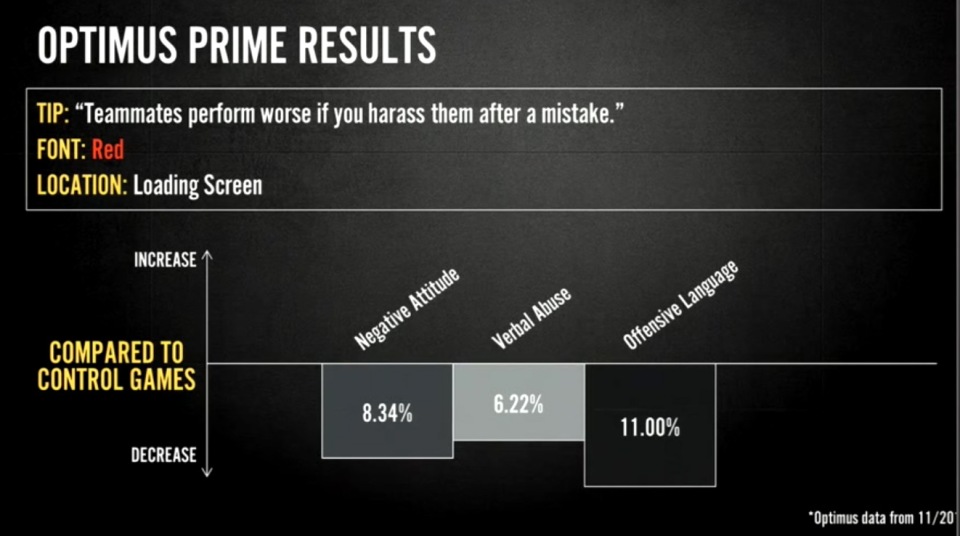

The Optimus Experiment (Maher, 2016) researched the possibility of reducing negative behaviour through priming, a psychological technique that attempts to influence behavioural outcomes based on what is presented to the person beforehand. In this experiment, players were primed with messages such as ‘Players who cooperate with their teammates win more games’ and ‘Teammates perform worse if you harass them after a mistake’ during loading screens and in-game. The colour of these messages was also manipulated as red is associated with punitive consequences, while blue is considered to be more ‘inspirational’ and encourages creative thinking (Mehta & Zhu, 2009; Elliot et al., 2007; Atkinson, 1957).

Data collection for The Optimus Experiment occurred in over ten million games of League of Legends (Hsu, 2015). Usernames were not stored in the experiment for data protection reasons, so unfortunately there is no way to know the final sample of the study as a player could have been involved in multiple games. For speculative purposes, the final sample could vary anywhere between 20 million-100 million participants. 10% of games during the data collection period did not receive any messages and were used as a control group for comparison.

Messages such as ‘Teammates perform worse if you harass them after a mistake’ in red, and ‘Players who cooperate with their teammates win more games’ in blue reduced the number of in-game reports compared to the control group.

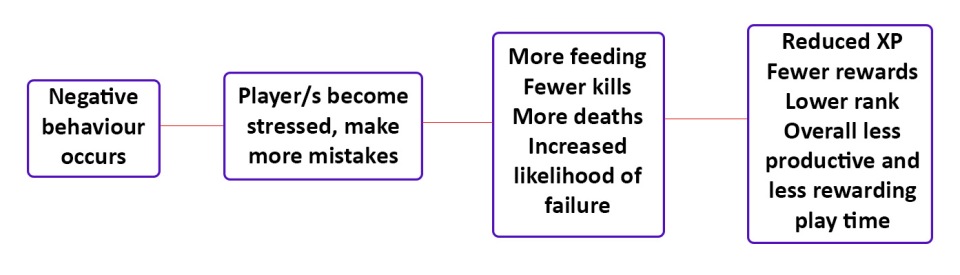

This is very interesting for the future of online gaming behaviour. As previously discussed, some people simply have the propensity to cause harm through a number of social, socioeconomic and personal factors. For these people, simply telling them not to hurt someone’s feelings may not be an effective intervention. Instead, this research seems to suggest that negative behaviour is reduced if the problem is presented as a cost-benefit analysis. I have created a diagram below to demonstrate this:

It seems possible to reduce negative behaviour in gaming if it is presented as something that will cost people time, success and resources. This would be easy and cost-effective for game developers to achieve by implementing messages in-game and in loading screens that raise awareness of this cost-benefit analysis.

Before concluding, I would quickly like to address two additional points for future interventions.

The first point is that I fully acknowledge that some people, quite simply, want to watch the world burn. It will not matter to these people if their behaviour costs them, they will be willing to engage in it regardless. To combat this, I would recommend testing a priming message that acknowledges that some people just want to behave badly for the fun of it. This may help people with a high locus of control reframe the issue as something that is not their fault.

The second point comes from something Dr Lin noticed during his time at Riot Games:

“The vast majority [of reports were] from the average person just having a bad day,” says Lin. They behaved well for the most part, but lashed out on rare occasions.

– Mayer, 2016

It is possible that an otherwise friendly person that is being pushed to their limits offline may lash out while enjoying the luxury of anonymity on the internet. Pointing this out may once again be helpful to those with a high locus of control as the problem becomes someone reaching their breaking point, not them needing to uninstall the game.

Thank you very much for reading and please have a nice day.

Summary

- Unhappy with the unhelpful and even exploitative nature of gaming harassment discussions, I decided to use research and psychology to provide helpful information for players and game developers on how to manage and reduce this negative behaviour.

- Muting and blocking are powerful tools as online gaming harassment occurs in a vacuum unlike traditional offline bullying. Not engaging with the individual transfers the balance of power from them to you. However, muting and blocking may not be effective for those with internalising behaviours, a high locus of control or with mental health difficulties as they may use harassment as justification to self-flagellate.

- Evidence suggests that the likelihood of winning an online game where harassment is taking place is reduced. While at Riot Games, Dr Lin conducted a study within over 10 million League of Legends games where information stating this was included. Equipping players with this knowledge led to a reduction in negative online gaming behaviour.

- A key intervention for reducing negative online behaviour is framing harassment as a cost-benefit analysis. Players should be made aware that if they engage in negative behaviour, they are more likely to lose and will then receive fewer in-game rewards. This is a cost-effective strategy for game developers as it simply involves displaying text in-game or during loading screens.

- Future research should investigate the benefit of adding sentences that acknowledge the sometimes chaotic nature of humanity and the possibility that the harasser is having a bad day. This helps shift blame away from the person receiving the harassment and should be beneficial for mental health.

References

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64(6), 359–372

Barboza, G. E., Schiamberg, L. B., Oehmke, J., Korzeniewski, S. J., Post, L. A., & Heraux, C. G. (2009). Individual characteristics and the multiple contexts of adolescent bullying: An ecological perspective. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 101–121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9271-1

Bornstein, M. H., Hahn, C. S., & Haynes, O. M. (2010). Social Competence, Externalizing, and Internalizing Behavioral Adjustment from Early Childhood through Early Adolescence: Developmental Cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22(4), 717–735. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000416

Bradshaw, C. P., Sawyer, A. L., & O’Brennan, L. M. (2009). A social disorganization perspective on bullying-related attitudes and behaviors: The influence of school context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 43, 204–220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10464-009-9240-1

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25, 65–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0020149

Craig, W. M., & Pepler, D. J. (1998). Observations of bullying and victimization in the school yard. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 13, 41–59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/082957359801300205

Elliot, A. J., Maier, M. A., Moller, A. C., Friedman, R., & Meinhardt, J. (2007). Color and Psychological Functioning: The Effect of Red on Performance Attainment. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 136(1), 154–168.

Ferguson, C. J., San Miguel, C., & Hartley, R. D. (2009). A multivariate analysis of youth violence and aggression: The influence of family, peers, depression, and media violence. The Journal of Pediatrics, 155, 904–908. e3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.06.021

Harris, K. J., Kacmar, K. M., & Zivnuska, S. (2007). An investigation of abusive supervision as a predictor of performance and the meaning of work as a moderator of the relationship. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 252-263.

Hsu, J. (2015). Inside the largest virtual psychology lab in the world. Retrieved April 17th, 2018, from https://www.wired.com/2015/01/inside-the-largest-virtual-psychology-lab-in-the-world/ .

Kaltiala-Heino, R., Rimpelä, M., Rantanen, P., & Rimpelä, A. (2000). Bullying at school—An indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 661–674. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0351

Kwak, H., Blackburn, J., & Han, S. (2015). Exploring cyberbullying and other toxic behavior in team competition online games. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 3739-3748). ACM.

Ma, L., Phelps, E., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2009). Academic competence for adolescents who bully and who are bullied: Findings from the 4-H study of positive youth development. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29, 862– 897. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272431609332667

Maher, B. (2016). Can a video game company tame toxic behaviour? Nature, 531, 568-571.

Mehta, R., & Zhu, R. J. (2009). Blue or Red? Exploring the Effect of Color on Cognitive Task Performances. Science, 323, 1226–1229.

O’Connell, P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: Insights and challenges for intervention. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 437–452. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0238

Pepler, D., Craig, W., & O’Connell, P. (2010). Peer processes in bullying: Informing prevention and intervention strategies. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, & D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective (pp. 469–479). New York, NY: Routledge.

Piaget, J., & Cook, M. T. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. New York, NY: International University Press.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General & Applied, 80(1), 1–28.

Swearer, S. M., & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis–stress model. American Psychologist, 70(4), 344-353.

Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., Henle, C. A., & Lambert, L. S. (2006). Procedural justice, victim precipitation, and abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology, 59, 101-123. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00725.x

Vaughn, M. G., Fu, Q., Bender, K., DeLisi, M., Beaver, K. M., Perron, B. E., & Howard, M. O. (2010). Psychiatric correlates of bullying in the United States: Findings from a national sample. Psychiatric Quarterly, 81, 183–195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11126-010-9128-0