The Psychology of Gaming Disorder

On June 18th 2018, the International Classification of Diseases 11 (ICD-11) was published by the World Health Organisation. This diagnostic manual, currently only available to stakeholders for adaptation, has legitimised ‘Gaming Disorder’ as a mental health disorder. On the same day, a video was published on the World Health Organisation’s YouTube channel providing context for the controversial decision:

Gaming Disorder has now been added because of very clear scientific evidence that it has characteristic signs and symptoms, and there is need and demand for treatment from many regions of the world…But let me just add that everybody who indulges in gaming from time to time doesn’t have this disorder. In fact, it’s only a minority of people who game who will satisfy the strict criteria for Gaming Disorder in ICD-11.

– Saxena, 2018

The specific attention paid to Gaming Disorder in the video is a result of a prolonged period of controversy surrounding the diagnosis. I originally wrote this article before the official legitimisation of Gaming Disorder. Now that it is legitimised, I have made a few changes to it.

The purpose of this article is to educate people on what Gaming Disorder is and why it was such a contested inclusion in the ICD-11. This will include what academics have to say about it, some controversies on the diagnosis, and what the future of Gaming Disorder may look like.

There will be a summary at the bottom for those who do not wish to read everything. Please enjoy!

Context

Gaming Disorder is a mental health disorder included in the World Health Organisation’s ICD-11, a diagnostic manual of physical and mental health disorders. The diagnostic criteria includes:

…a pattern of persistent or recurrent gaming behaviour (‘digital gaming’ or ‘video-gaming’), which may be online (i.e., over the internet) or offline, manifested by: 1) impaired control over gaming (e.g., onset, frequency, intensity, duration, termination, context); 2) increasing priority given to gaming to the extent that gaming takes precedence over other life interests and daily activities; and 3) continuation or escalation of gaming despite the occurrence of negative consequences…

Please note that the ICD-11’s Gaming Disorder is different from the DSM-V’s ‘Internet Gaming Disorder’ (IGD). IGD is included in the DSM-V as a ‘condition for further study’, meaning that they would like researchers to explore the validity of the criteria before legitimising it as a diagnosable mental health disorder. There is no trial period for Gaming Disorder: once the ICD-11 is published with Gaming Disorder, it can be diagnosed.

Gaming Disorder was added to the ICD-11’s beta draft list in approximately September 2016 and was available to view as a frozen beta draft release in October 2016. Although the publication of the ICD-11 has experienced delays since 2012, the WHO are aiming for a publication date in the second half of 2018. This was indeed achieved with a release date of June 18th 2018.

The Research

This is the part of ‘The Psychology of…’ where I bombard you with research, tell you what the statistics mean, tell you what the overall conclusion is and hopefully leave you feeling happy and educated.

Except…there is no research.

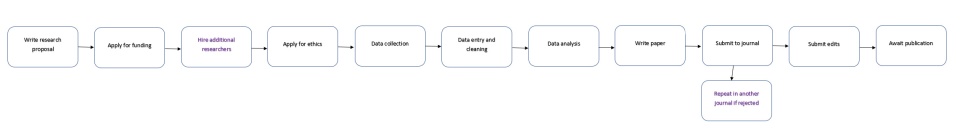

With the introduction of Gaming Disorder in September 2016 and a publication date of 2018, there has been no time to conduct research on the proposed definition and criteria for Gaming Disorder. As a researcher myself, allow me to demonstrate the work that goes into conducting and publishing research.

As for how long this process takes, it is impossible to define. Each of these steps can take months, perhaps years if data is collected longitudinally. It is no surprise to me that no research has been published on Gaming Disorder yet considering how long the research process takes.

However, that does not mean that academics are staying silent on the matter. Several open letters to the WHO have been published following the beta draft inclusion, each with their own important arguments for why Gaming Disorder should and shouldn’t be included. As I am passionate about bringing academia to the public, I am going to summarise these open letters so gamers can understand the current academic climate surrounding Gaming Disorder.

I would like to state that I am beginning with the ‘against’ side of the inclusion of Gaming Disorder as the first article I will be summarising is discussed in each subsequent article. I am doing this for organisation and clarity, not for bias.

Gaming Disorder – Against

The first open letter to come out against the inclusion of Gaming Disorder in the ICD-11 is ‘Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder Proposal’ (Aarseth et al., 2016). This paper is authored/signed by a whopping 26 academics spanning 24 universities/research institutes.

This letter is supported by a number of academics that work on exploring the positive and negative aspects of technology use, with four of the authors writing their doctoral thesis on addictive patterns of gaming. The authors are transparent in wanting some form of official recognition for pathological gaming, but believe that the current move by the WHO is far too premature.

Some gamers do experience serious problems as a consequence of the time spent playing video games. However, we claim that it is far from clear that these problems can or should be attributed to a new disorder, and the empirical basis for such a proposal suffers from several fundamental issues.

– Aarseth et al., 2016

The first issue cited is a lack of consensus on what Gaming Disorder should look like due to a lack of research on the topic. This is particularly true of studies conducted with clinical samples of pathological game playing due to low sample sizes.

The second issue cited is the overreliance on gambling criteria to try to develop a criteria for Gaming Disorder. If an addiction is behavioural rather than biological, this is less straightforward than simply saying someone is addicted to a substance and experiences withdrawal without it. As a result, the authors feel that the criteria for Gaming Disorder is underdeveloped and too similar to criteria for gambling addiction.

One example that is provided is thinking about video games during your leisure time. Being excited to leave work and hunt monsters with your friends is not inherently similar to being excited to leave work and spend hours in a dark room gambling away your paycheque on slot machines. This, combined with the fact that there is no research which validates the criteria for Gaming Disorder, means we do not know if the criteria is specific or valid enough to represent what addictive gaming looks like.

The third issue cited is the fact that addictive gaming seems to often be accompanied with other mental health disorders such as depression or anxiety disorders (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014); this is called ‘comorbidity’. It is argued that the suggested criteria for Gaming Disorder may not be robust enough to detect whether someone is playing games for reasons such as a distraction from depressive symptoms or gaining social contact that their undiagnosed Social Anxiety Disorder prevents them from doing. I have seen this practice referred to as ‘Bed Syndrome’. If someone is depressed and spends all day in bed, you do not diagnose them with Bed Syndrome, you look at why they spend all day in bed. There is a fear that if a person’s gaming is focused on and not the person themselves, this will lead to inadequate mental health treatment.

Continuing on with fears of inadequate mental health treatment, Professor Andrew Przybylski, Senior Research Fellow at Oxford Internet Institute, spoke about the premature pathologising of gaming. While this interview is in regards to Internet Gaming Disorder, the implications are the same for Gaming Disorder which will be legitimised as a mental health disorder before IGD.

In the mental health system, a diagnosis is a vehicle which helps steer you towards a correct and appropriate treatment path. The WHO has not specified the treatment plan for Gaming Disorder, but pre-existing treatment plans have Professor Przybylski concerned:

Detox camps are very worrying to me as a scientist because they have no scientific basis, many of those who run them have financial conflicts of interest when they comment in the press, and there have been a number of deaths at these facilities.

– Przybylski, 2017

Research conducted by Przybylski and colleagues (Weinstein, Przybylski, & Murayama, 2017) supports the idea that pathological gaming may be a method of distracting from other life difficulties rather than being the difficulty itself. In a study of those who believed they met the criteria for Internet Gaming Disorder, there was a significant relationship between the IGD criteria and feeling incompetent, powerless and feeling like they do not belong. After a six-month follow-up period, those who felt more competent, choiceful and felt a sense of belonging no longer met the criteria for IGD and had better self-reported health.

Finally, Przybylski fears that the pathologising of a popular hobby may lead to even further stretching of a mental health system that is already overstretched in many countries.

It is very serious stuff. Opening the door to pathologizing one of the world’s most popular recreational activities risks stigmatizing hundreds of millions of people and shifting resources in an already overstretched mental health systems over the breaking point.

– Przybylski, 2017

To summarise, the arguments against the inclusion of Gaming Disorder revolve around its lack of research, its lack of validity assessment, its lack of comorbidity assessment, its lack of treatment outline and its overreliance on conventional gambling criteria.

Gaming Disorder – For

The first paper that I will be looking at which supports the inclusion of Gaming Disorder in the ICD-11 is ‘Inclusion of gaming disorder in the diagnostic classifications and promotions of public health response’ (Shadloo et al., 2017).

The argument is made that researchers are not trying to demonise regular behaviours like playing video games, and that this inclusion will not impact your everyday gamer. Instead, Gaming Disorder is made to help those who need it.

When articles started coming out about recognising Gaming Disorder as a mental health disorder, I saw many comments from people boasting that they would sit at home all day and play video games to get ‘disability bux’. However, this paper makes the situation sound a lot less amusing:

…clinicians from our country face increasing treatment demand for problematic cases who suffer from significant social/financial/occupational, or school function impairment due to gaming…But unfortunately, due to ambiguities around the diagnosis, treatment protocols have remained underdeveloped and clients and their families cannot benefit from insurance coverage.

– Shadloo et al., 2017

This argument really makes it sound like a vicious cycle. Because Gaming Disorder is not legitimate, countries where mental health access is dictated by insurance cannot treat people who may be addicted. Because Gaming Disorder is not legitimate, a treatment protocol cannot be developed. Because a treatment protocol is not developed, scary ‘detox camps’ funded by external agencies remain as scary and prevalent as ever.

In a nutshell, the authors of this paper want Gaming Disorder to be legitimised so: 1) people can get access to mental health treatment through their insurance, and 2) development can begin on healthy, safe treatment options away from scary and dangerous detox camps. However, one thing this paper does believe is that the WHO has done a poor job in validating the diagnostic criteria.

The validity of diagnostic guidelines is one of the main concerns of Aarseth et al. and the diagnostic validity of gaming disorders is challenged several times throughout their letter. Although this does not defy the concept of the disorder, we believe that this is a sound concern and should be meticulously exercised.

– Shadloo et al., 2017

In ‘ICD-11 Gaming Disorder: Needed and just in time or dangerous and much too early?’ (van den Brink, 2017), the author empathises with the tricky situation that the WHO is in. The DSM-V is able to enjoy the luxury of researching Internet Gaming Disorder without any backlash due to IGD being included in the ‘conditions for further study’ category. However, the WHO does not have this category. Instead, they must decide whether to prioritise validating and researching their diagnostic criteria or giving people access to mental health care through their insurance.

‘Problematic gaming exists and is an example of disordered gaming’ (Griffiths et al., 2017) argues that the act of publishing a diagnostic criteria for Gaming Disorder provides researchers with a clear goal to work on and assess. This could be viewed as somewhat of a vicious cycle. Aarseth et al. (2016) argue that there is no consensus in video game addiction research, but Griffiths argues that a consensus can be worked towards if there is “…an officially recognized and unifying diagnostic framework”, something which Gaming Disorder provides. Similarly to Shadloo et al., Griffiths believes Gaming Disorder will help the very small minority rather than stigmatising the majority.

While being socially conscious and aware that gaming is a pastime activity which is enjoyed by many millions of individuals, most of whom will never develop any problems as a consequence of engaging in gaming, we need to be respectful of the problematic gamers’ experiences and offer the empirical foundations for targeted prevention efforts and professional support.

– Griffiths et al., 2017

To summarise, the inclusion of Gaming Disorder will allow for people to receive treatment for video game addiction through health insurance, will work towards a healthy treatment plan free from ‘detox camps’, and will give researchers a goal to work on and validate.

Gaming Disorder – Miscellaneous

I will quickly discuss one paper that does not take a strong stance one way or the other, but makes a good point about Gaming Disorder.

‘The relationship between gaming disorder and addiction requires a behavioral analysis’ (James & Tunney, 2017) argues that ‘gaming’ is simply too reductionist and that greater attention needs to be paid towards the addictive aspects of games such as mobile games. In my article on the psychology of loot boxes and microtransactions, I pointed out how certain game genres are more addictive and can encourage microtransactions more than other genres. As this point has a research basis to it, I believe it deserves more exploration.

Controversy

During my research on Gaming Disorder, I came across quite an interesting and perhaps controversial series of press statements regarding Gaming Disorder from WHO advisors.

In the summer of 2017, Polygon published an article discussing Gaming Disorder and what it could mean for gamers. Dr Geoffrey Reed, a member of the WHO advisory board, had this to say to Polygon:

Dr. Geoffrey M. Reed…says that he is being petitioned by politicians to make sure gaming addiction is included.

“Not everything is up to me,” Reed wrote to one of Bean’s co-authors in an email from August 2016. “We have been under enormous pressure, especially from Asian countries, to include this.”

However, Dr. Vladimir Poznyak, coordinator of the Management of Substance Abuse department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse for the WHO, had something completely different to say:

“There was not any pressure from WHO Member States to include ‘gaming disorder’ in the [ICD],” he wrote Polygon in an email, “and the decision made was based entirely on the available scientific evidence and experiences with such health conditions in different countries, not limited to Asian countries.

– Poznyak, 2017

I don’t really know what to make of this. At best, this is miscommunication within the WHO and one very dissatisfied member of the advisory board. At worst, it is something more sinister.

The Future

ICD-11 and Gaming Disorder are here. We’ve talked about the pros, we’ve talked about the cons, now we need to talk about the future.

In my clarification piece on Gaming Disorder, I briefly outlined the future for Gaming Disorder:

Furthermore, a hypothetical publication date of June 2018 does not mean that clinicians will immediately begin using ICD classifications. Each country has to make a decision on what classification systems to use and when to transition to these classification systems. For example, despite the ICD-10’s release date of 1992, America did not transition to ICD-10 codes from ICD-9 codes until October 1st, 2015.

However, more information on this process comes from the admin of DX Revision Watch, a site which catalogues changes made to the ICD-11 and DSM-V. This information comes courtesy of a Twitter thread which I will put in prose for ease of reading:

ICD Revision’s Dr Chris Chute told me, in Feb ’17, it will likely be five or six years before member states have evaluated the new edition and are prepared for transition. [It] will take [the] USA longer as they need to develop a clinical modification and also develop an ICD-11-PCS. Member states will evaluate, prepare their health systems and transition to the new edition at their own pace.

There will be no WHO mandated date for adoption of the new edition, though they will not support ICD-10 indefinitely. So for some years, post release, WHO will be collecting and aggregating data recorded using both ICD-10 and ICD-11. NHS UK has yet to project a date by which ICD-11 is planned to be implemented.

Dr Chris Chute (chair, MSAC), Feb 2017: “…What is produced say in 2018 will continue to evolve, ICD11 is designed for graceful evolution. It may differ in substantial ways by the time the first country implements it, say 5-6 years from now from what is put forth in 2018…”

– DX Revision Watch, 2018

To summarise, it will be a number of years before the ICD-11 is used and member countries are placed under no time restriction for moving on to the ICD-11. Before moving on, each country will assess the proposed criteria and suggest changes based on evidence. As such, what is published on Gaming Disorder in 2018 is likely to change as more countries assess the ICD-11 within clinical samples.

Thank you very much for reading and please have a nice day.

Summary

- Gaming Disorder was included as a mental health disorder in the ICD-11 in June 2018. The criteria includes frequent video gaming, giving priority to video gaming over other activities and repeated gaming despite negative consequences.

- Due to the length of time required to conduct and publish research, no study exists which assesses the validity of the diagnostic criteria. While we await research findings, academics have been publishing letters and papers discussing the pros and cons of the inclusion.

- The cons of including Gaming Disorder include: a lack of research evidence, a lack of validation for the Gaming Disorder criteria, no clear treatment path, no consensus among researchers about what Gaming Disorder should look like, criteria which is unjustly similar to gambling addiction, and a fear of overburdening the mental health system with vague diagnostic criteria.

- The pros of including Gaming Disorder include: giving addicted people access to mental health care through health insurance, working towards a healthy and safe treatment option away from dangerous ‘detox camps’, and working towards a consensus on Gaming Disorder.

- Some academics would also like to see ‘gaming’ expanded on to recognise that different genres can be more addictive than others (such as mobile games).

- There was some controversy in 2017 as a member of the WHO advisory board stated that the WHO was under political pressure to include Gaming Disorder in the ICD-11. This statement was denied by another WHO member.

- When Gaming Disorder is included in the ICD-11, it is likely that changes will be made to the criteria after global research and assessment.

References

Aarseth, E., Bean, A. M., Boonen, H., Colder Carras, M., Coulson, M., Das, D., … & Haagsma, M. C. (2016). Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 267-270.

Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Lopez-Fernandez, O., & Pontes, H. M. (2017). Problematic gaming exists and is an example of disordered gaming: Commentary on: Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal (Aarseth et al.). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 296-301.

James, R. J., & Tunney, R. J. (2017). The relationship between gaming disorder and addiction requires a behavioral analysis: Commentary on: Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal (Aarseth et al.). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 306-309.

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351-354.

Shadloo, B., Farnam, R., Amin-Esmaeili, M., Hamzehzadeh, M., Rafiemanesh, H., Jobehdar, M. M., … & Rahimi-Movaghar, A. (2017). Inclusion of gaming disorder in the diagnostic classifications and promotion of public health response: Commentary to the “Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal”: A perspective from Iran. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 310-312.

van den Brink, W. (2017). ICD-11 Gaming Disorder: Needed and just in time or dangerous and much too early? Commentary on: Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal (Aarseth et al.). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 290-292.

Weinstein, N., Przybylski, A. K., & Murayama, K. (2017). A prospective study of the motivational and health dynamics of Internet Gaming Disorder. PeerJ, 5, e3838.

One Comment

Mike Phalin

Thank you for all your work on this.