The Longitudinal Study of Gaming and Sexism

The Daily Telegraph published an article arguing that sexy video game characters harm children and promote sexist ideas of women (NSFW warning). This argument was made without any evidence into the effects of video games on sexist beliefs.

Back in 2015, I wrote an article breaking down a longitudinal study of video games and sexist attitudes. I am migrating this article to my website to introduce some research into the debate, but please note that this is an earlier piece of mine. My new breakdowns are formatted differently now, please consider checking them out if you are interested in video game research.

As usual, there is a summary below if you do not wish to read everything. Enjoy!

Methodology — The Bad

Participants didn’t have an awful lot of choice when recording video game genres. According to the appendix, participants were asked how often they played and how much they liked ‘Role-playing games’, ‘First-person shooter games’ and ‘Other action games’. Participants had the option to say that they didn’t play these types of games, but they had no option to volunteer their own categories. I find it a bit hypocritical that they single out fighting game women in the abstract for the study, yet do not even assess this genre.

However, the researchers acknowledge this limitation and suggest it as an avenue for future research. I would also play Devil’s Advocate on their behalf and justify it on the basis that they looked at each category’s relationship with sexist beliefs. Things get a bit messy when participants start volunteering their own categories (“What do you MEAN you haven’t heard of Touhou? Are you some sort of casual?”), so I can understand them trying to control their categories for individual analysis.

This part is Criticism 101, but always beware of taking one population’s findings and applying them globally. As this study was conducted with German participants, what applies to Germany may not apply to Japan, Sweden etc.

Methodology — The Good

The sample size is pretty good: 824 participants (464 male, 360 female) over a three year time period in a naturalistic setting (telephone conversation at home). I do like that it’s relaxed and natural rather than bringing people into an artificial environment and asking them to answer questions on sexism.

902 participants were involved in all three stages of the study, but the researchers took a no-nonsense approach to managing their data and deleted anyone who missed out even one question (known as ‘listwise deletion’). This is arguably the best practice for handling missing data, but it can be scary as you can end up losing lots of participants. Credit where credit’s due for trying to maintain the best quality of data possible.

The sexism scale used is very reliable. I wanted to single this out because the researchers specified condensing the scale for ease in telephone interviews. This can be a nightmare as removing questions or simply re-wording questions can make them very unreliable and inappropriate to use in research (I actually know this feeling…). The fact that they shortened the scale and it retained high reliability is a good sign that they were measuring important aspects of sexism.

Now on to my favourite part, the statistics!

Structual Equation Modelling: The ‘Story’ of Sexism

Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) is one of my favourite types of statistical analysis. In layman’s terms, SEM tests a ‘model’ which you have developed based on theory and/or evidence. Let’s take the current study for example. The researchers hypothesized that sexist attitudes are related to video game use and can predict future video game use. While testing this, they also wanted to look at this relationship when age and education were factored in. Not only that, but they wanted to explore the relationship for sexist attitudes and video game use during the different time points.

To massively condense that, the story would be “I think sexist attitudes relate to video game use, encourage video game use and that the two are consistent during time periods”.

Confused? Could you use a diagram? Thankfully, SEM is full of diagrams!

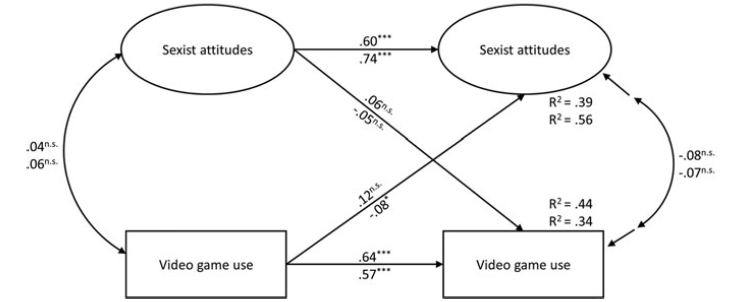

This is the SEM diagram presented in the paper. Don’t worry about the lines and numbers for now, I will break these down soon. Instead, I want to focus on the ‘fit’ of the model. Model fit will tell us how accurate our theories are in predicting what we want to predict. For this case, SEM will tell us how good sexist attitudes are in explaining video game use and how influential video game use is to sexist attitudes. The fit criteria is presented below:

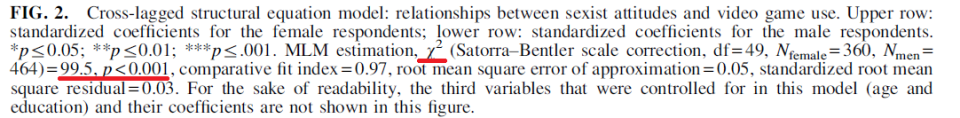

The section I have underlined is referred to as the ‘Chi-Square Fit Criteria’. This tells us whether our model can be significantly improved upon. A tiny Chi-Square value that is non-significant (p > .05) says to us “Wow, you were right! Video game exposure has a huge impact on sexist attitudes and vice versa. Video games explain sexism so well that there is absolutely nothing more we can add to our story that will explain sexism.”

This is one of the largest, most significant Chi-Square values I’ve ever seen. For reference, here is some from my own research:

This model is ineffective at explaining sexism and video game consumption, and massive improvements can be made to it by considering a wealth of other factors. In a nutshell, the argument that video games facilitate sexism is not statistically sound and is absurdly reductionist.

As promised, I will now break down the arrows and numbers. I will also discuss the relationship between age and education that was left out of the diagram.

- Sexist attitudes remain consistent across time, as does video game consumption. However, the authors noted that there were gender differences — women were more consistent gamers than men.

- Video game use was not related to sexist attitudes between any time points. However, there was one significant correlation across time points. Video game use for males lead to a significant decrease in sexist attitudes between two time points. However, the authors rightfully comment that while the relationship is significant, the change between timepoints is so small that they consider it ‘negligable’.

- There was no relationship between genre of game preferred, sexist attitudes or gender.

- Males hold less sexist attitudes as they get older, but this is unaffected by video game consumption. More educated females play more games than less educated, but this is not related to sexism.

Thank you for reading and happy gaming. ♥

Summary

- A longitudinal telephone study was conducted in Germany to explore the relationship between gaming, sexist attitudes and gender.

- This data was analysed using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), a data analysis technique that tests how well a ‘model’ (a selection of theories) explains the data.

- The model in this study was: ‘Video game use is related to sexist attitudes’.

- The SEM results show that this model is a terrible fit for the data, meaning that there are many other factors out there that predict sexist attitudes beyond video games.

- There was no relationship between genre of game preferred, sexist attitudes or gender.

- Males hold less sexist attitudes as they get older and this is unaffected by video game consumption. More educated females play more games than less educated, but this is not related to sexism.