Online Gaming Protects Against Poor Mental Wellbeing

While doing PhD work, I came across a paper titled ‘Video gaming in a hyperconnected world: A cross-sectional study of heavy gaming, problematic gaming symptoms, and online socializing in adolescents’. After seeing my favourite statistical test being used, I became curious and started reading. This paper is a fascinating read on the relationships between online gaming, loneliness and mental wellbeing. It also contains well-argued implications for the main diagnostic manual used by clinicians.

My aim is to break this research paper down in a format that is easy to understand for all. I will be adding in my own strengths and weaknesses to the study as it is always good to be critical. If you do not wish to read everything, I will include a bullet point summary at the bottom. Please enjoy!

Introduction

The paper begins by drawing attention to the inclusion of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) as a ‘condition for further study’ in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders 5 (DSM-V). Although the DSM-V encourages further research into IGD before recognising it as an official disorder, the preliminary criteria includes factors such as preoccupation with online games, requiring more time to play games, and using the game as a coping or escape mechanism.

Following this criteria, the authors put forth two arguments that will form the basis of the research. Firstly, they argue that the criteria is reductionist as it does not account for differing reasons and motivations for playing online games in particular. The distinction between online games and offline games is quite a clear one – the social component. This social component then feeds nicely into the second argument. If IGD is to be officially recognised as a disorder, it will be placed into the Addictions section of the DSM. Addictive behaviours such as gambling are typically mundane, repetitive behaviours that are carried out as a method of alleviating boredom, stress or low mood.

If gaming is to be recognised as an addiction, we must ask ourselves something – why only online games? Are offline games incapable of fulfilling the same purposes that online games do? Is the social component of gaming necessary in order for it to be considered an addiction and coping mechanism?

After pinpointing these unexplored questions, the researchers argue that it is necessary to identify ‘classes’ of video game player based on their gaming lives (online and offline games), and their social lives offline and online. Using these classes of video game player, four main hypotheses will be tested:

- If we treat gaming purely as an addiction, then people who spend the most time playing video games will have the lowest amount of time spent talking to people. After all, they’ll just want to ignore people and engage in the addictive behaviour.

- Psychological wellbeing will differ between classes of video game player.

- Classes that are high in online social interaction will have better online friendship quality.

- Having high quality online and/or offline relationships will be related to more positive mental wellbeing.

Methodology

The data from this study comes from the Monitor Internet and Youth study, a longitudinal study of 12,348 young people aged 13-16 in the Netherlands between 2009-2012. Data was collected from the same young people every year between 2009-2012. As usual, you can make the argument that you should be wary when extrapolating the findings of this study to anywhere apart from the Netherlands. I was prepared to criticise the study for its relatively young sampling age, but further research informs me that this age group represents the mid-point for the emergence of IGD (12-20 years old).

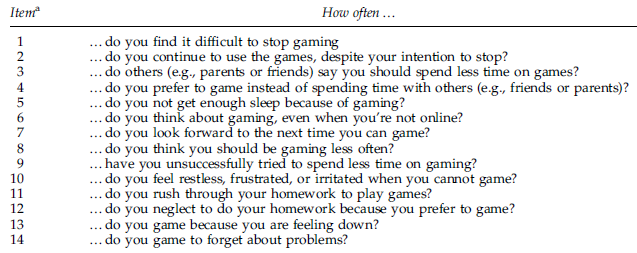

Young people were asked how many hours per day and days per week they spent: using instant messaging services, browsing social networks, playing multiplayer online games, playing browser games (Note: This didn’t really relate to anything and will thus be left out), and playing offline games. Young people were classified as ‘high’ in these behaviours if they spent more than four hours per day, six days per week engaging in the behaviour. Video game addiction was measured using the Video game Addiction Test (VAT) which can be seen below.

All questions load on to one factor with factor loadings between 0.62 and 0.78, and the scale has excellent reliability with α = 0.93. In layman’s terms, the scale consistently measures video game addiction and there is little ‘noise’ in the content of the questions.

Depressive symptoms, loneliness, social anxiety and self-esteem were measured with industry-standard, reliable scales such as Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem scale. Offline and online friendships were assessed with the Network of Relationships Inventory. This scale asked young people how often they spoke to friends within their network, ranging from ‘Never’ to ‘Very Often’. From this scale, two categories of friendships were created: low/high quality of online friendships and low/high quality of real-life friendships. Please note that these categories are not mutually exclusive – it is possible to have both high quality online and real-life friendships.

Statistical Analysis

Now this is where it gets juicy. I mentioned above that this study uses my favourite statistical analysis, an analysis known as Latent Class Analysis (LCA). In LCA, rather than creating arbitrary categories and collecting data on them, you collect your data and use it to create data-driven, person-centred categories.

Let me explain. I ask a group of people whether they play six games: Street Fighter, Final Fantasy, Tekken, Call of Duty, Halo and Dragon Quest. I run an LCA using all of this data. The LCA then tells me that it looks like there are three categories that exist in this data. Category 1 is people who play Street Fighter and Tekken, Category 2 plays Call of Duty and Halo, and Category 3 plays Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest. I then label Category 1, 2 and 3 ‘Fighting game players’, ‘First person shooter players’ and ‘JRPG players’ respectively. Voila, I have naturally-occurring, data-driven categories.

This is what this study will be doing: exploring categories of gamers based on what games they play, how often they play them and how much they talk to other people. LCA requires a program called MPlus to run, and MPlus absolutely does not tolerate missing data.

Remember how I said data was collected from 12,348 young people? Well the analysis will be conducted with 9,733 young people as MPlus chews up and spits out anyone with any missing data. The analysis sample contains 51.2% females and 82.1% Dutch nationals, with an average student age of 14.1.

It is common for LCAs to be divided by gender, and this study is no exception. As such, I will be reporting the genders’ findings separately.

Results – Male

The LCA suggests that there are six distinct types of male video game players: Normative, Extensive, At-Risk, Social Engaged, Social At-Risk and Problematic. I will discuss each class and their properties individually.

Normative: 52.5% of males. For lack of a better term, the ‘normies’. These males do not really play video games very often. Nothing much is really said about this group as more attention is (understandably) paid to other groups.

Extensive: 27.3% of males. This group of males plays a little more video games (both online and offline) than the normative group. This population is more likely to experience depression symptoms and social anxiety compared to the normative group. They are also significantly more likely to report being lonely and having fewer online friends than the normative group.

At-Risk: 10.3% of males. This group is the least social group of gamers: they spend little time talking to others online, are significantly more likely to have no online friends, and have the second-highest video game addiction scores. This group is significantly more likely to report depressive symptoms, loneliness and social anxiety than the normative group.

Social Engaged: 5.1% of males. These guys love to game, they love to talk and they hold a very interesting finding. You will notice that all male gamers so far have experienced significantly more depresseive symptoms than the normies. Social Engaged gamers are no exception…at first. The interaction between being a Social Engaged Gamer (SEG) and depression scores is indeed significant, but when the interaction becomes SEG x depression scores x quality of friendships, it is no longer significant. Gamers with good quality friendships do not experience as many depressive symptoms.

Social At-Risk: 2.0% of males. Social At-Risk males are a lot like Social Engaged males: they talk a lot and they play a lot of games (both offline and online), just on a larger scale. They experience depressive symptoms just like the rest of their male gaming companions, but they do not experience loneliness, social anxiety or struggle with their self-esteem.

Problematic: 1.3% of males. These guys play the most online games and have the highest video game addiction scores. They are second in offline video gaming to Social At-Risk and are third overall in online social interaction. This is the group of guys that the DSM-V dictates should be the loneliest, most depressed, most anxious and should have the lowest self-esteem.

But they don’t. Granted, they experience depressive symptoms like the rest of male gamers, but they are not lonely, they are not anxious and they do not have low self-esteem. However, their relationship between high online friendships and low real-life friendships is significant.

It seems that these males have few real-life friends, but have compensated for it by making friends online through games. The time that they spend talking and playing video games with others seems to be protecting their wellbeing.

Results – Female

In comparison to six latent classes for males, females have three latent classes: Normative, Social Engaged and At-Risk. Again, these results will be discussed separately.

Normative: 83.2% of females. The ‘normies’ with little video game consumption and the comparison group for the remaining two classes.

Social Engaged: 10.9% of females. This group of females enjoys playing online games, but has a slight preference for offline games. This group is quite interesting as they actually report less loneliness and social anxiety than the female normative groups. They also report higher quality friendships both online and in real-life, but they experience lower self-esteem than the normative group.

At-Risk: 5.8% of females. These females have a video game addiction score similar to the male at-risk group. They enjoy their online games, but have a very slight preference for offline games and prefer to talk much less than the Social Engaged group. This group of females experiences more depressive symptoms than the normative group, but there is no significant relationship with loneliness, social anxiety or self-esteem scores.

Discussion

Let’s revisit the hypotheses of the study.

If we treat gaming purely as an addiction, then people who spend the most time playing video games will have the lowest amount of time spent talking to people. After all, they’ll just want to ignore people and engage in the addictive behaviour.

Based on the evidence, we cannot treat video game consumption as a straightforward addiction – people have different motivations to play. Male Social At-Risk and Social Engaged gamers love to talk to others, while Problematic gamers are rewarded in online games with online friendships to compensate for poor offline relationships. Being a video game loving female is so rewarding that they are less lonely and anxious than their normative counterparts.

Psychological wellbeing will differ between classes of video game player.

We can accept this hypothesis as non-social gaming classes were associated with lower levels of psychosocial wellbeing.

Classes that are high in online social interaction will have better online friendship quality.

We can partially accept this hypothesis as the most social class of female (Social Engaged Gamers) had the highest quality of both offline and online relationships. While Problematic males benefit from online friends, it must be acknowledged that they were the third most social class.

Having high quality online and/or offline relationships will be related to more positive mental wellbeing.

Again, we can partially accept this hypothesis in males. Male Social Engaged Gamers experienced the same level of depressive symptoms to their gamer counterparts when friendship was ignored. When quality of friendship was added into the equation, depression scores dropped.

The remainder of the discussion section is dedicated to the study’s shortcomings and recommendations, such as young people potentially lying about how much they play video games. Personally, I feel this study is a success for three reasons:

- This was a study conducted with a large sample using well-validated measures and person-centred data analysis. This is a significant victory for video game research, which is typically conducted using small samples and poor methodology.

- This is not a paper designed to fearmonger or raise publicity for researchers with a controversial topic. This is a piece of research that is going to contribute to a diagnostic manual that will impact people’s lives with a diagnosis. I wholeheartedly believe that researchers should use their skills and knowledge to improve the world they live in and to help others. This is something I feel these researchers have achieved, something which cannot always be said about video game research.

- Finally, it shows that gamers aren’t really bad monsters. Yes, some of us are lonely. Yes, some of us don’t have as big of a friendship group as we dreamed we would have. But we have each other. We have our games and we have each other.

Thank you for reading and happy gaming! ♥

Bullet Point Summary

- As Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) has recently entered the most prevalent diagnostic manual used, researchers have argued that its classification ignores reasons to play games such as social support. These researchers explored the relationship between types of games played (online vs offline), social support and mental wellbeing.

- Analysed data from over 9,700 young Dutch people aged between 13-16 using Latent Class Analysis.

- Identified six different types of male gamers and three different types of female gamers.

- Male gamers who spend little time talking to others online while gaming are significantly more likely to be more lonely, anxious, self-conscious and report more depressive symptoms.

- Male gamers who talk with other gamers report less depressive symptoms than other male gamers.

- Male gamers who play a lot of games and have poor offline friendships, yet good online relationships are protected from loneliness, anxiety and low self-esteem.

- Female gamers who play online games are less lonely and anxious than girls who do not play games.